Whether students are reading poetry out loud, performing scenes from a play, or workshopping their own writing, I believe the English classroom becomes a community precisely when students inhabit the center as active co-creators. When students are invested in the pathway of their own learning and when they realize that their questions help guide our course, education transforms both the students and the teacher. This student-centered dynamic looks a lot like improvisational comedy, something I learned after a Duke Graduate School workshop on “Improv in the Classroom” and continued to learn through classes at a local theater. While a teacher should not necessarily be comedic, improvisational techniques can help create the active, open, and responsive spaces where learning can thrive. The fundamental rule of improv is “yes, and,” meaning that students affirm what another has contributed and then build off that contribution in a constructive way. In the classroom, embodying this principle transforms the teacher-student hierarchy into a space of co-learning, something I always strive for because classes become more interactive when students feel comfortable enough to risk failure. “Yes, and” means being open to new critical lexicons; it means recognizing the particular knowledge expertise of every student and finding ways to fruitfully connect that expertise with the course conversations; it means letting go of preconceptions to discover new lines of relation between disciplines, cultures, and backgrounds.

These new lines of relation began the very first class session in “The Poetry of Science,” a composition course focusing on the relationship between science and American literature. Although most of the twelve freshmen in this class were undeclared, their disciplinary interests were largely in the sciences, including engineering, pre-med, physics, and neuroscience. I started this course by challenging students’ conception of what a text is: on the first day, we analyzed a poem and a rock. The poem was Emily Dickinson’s “I Died for Beauty,” and the rock was a light brown parallel-bedded sandstone. I asked students to describe these two objects as succinctly and accurately as possible. In discussion, students quickly exhausted their critical vocabularies, and we realized the poetic descriptions were thematic, while the rock descriptions were even more reductive (one student merely wrote “brown”). Noting that literary critics and geologists tend to say three things about a poem and a rock, as soon as they encounter one, I introduced what I call an “Analytic Paraphrase.” The poetic paraphrase, a technique I learned from poetry critic Helen Vendler, involves defining the poem’s main mission, the sequence of speech acts, and the poetic form. The rock paraphrase involves defining the rock’s color, sedimentary structure, and compositional name. Our conversation was guided by several questions, such as: What does this activity tell us about the difference between a literary work and a specific science? Can we extrapolate anything from this activity by saying that it helps us think about the interconnected difference between literature and science in general? Every time students articulated a relationship between their poetic and rock readings, we plotted the contribution on the blackboard.

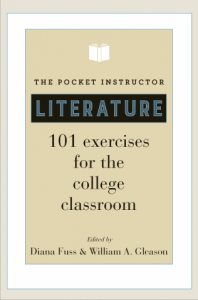

When I taught this interdisciplinary lesson, students were at first surprised that we could seriously consider sedimentary rocks as texts. Yet in discussion, they unearthed central issues regarding interpretation, such as intention, how we read “the human” vs. “the non-human,” what it means to be a multimodal medium, self-referentiality, representation, and—as Anna Wierzbicka writes in “Defining ‘the humanities’”—how science tends to orient itself toward “‘things’” and the humanities toward “‘people’” (34). One student mentioned how the poem was “produced,” while the rock was “received.” This led to a discussion of intention and ethics, and allowed us to excavate fundamental assumptions the students were making about the land: they assumed, for example, that they could say more about a poem than they could about a rock, as if the earth was not worth as much analysis or didn’t contain as much ambiguity. For students, rocks demanded less from their readers than poems did, being apparently outside the realm of emotions, values, and moral judgments. This lesson left a lasting impression on students, empowering them to describe how every author we read in class—from the eighteenth-century writings of poet Phillis Wheatley to the post-bellum fiction of neurologist S. Weir Mitchell—implicitly positions a relation between science and literature. In the end, students didn’t leave the class with their questions answered—they left the class with their sense of possibilities deepened, and a larger, more rigorous sense of the kinds of things poems say, the kinds of things rocks say, and the ethical implications enfolded in the saying. Princeton University Press selected my lesson for The Pocket Instructor: Writing, a forthcoming volume anthologizing active learning in the college classroom.

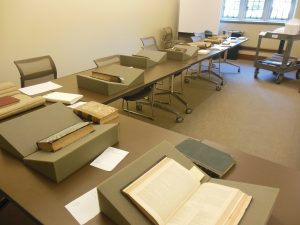

Believing knowledge is a public good, I’m constantly creating opportunities for my students to engage with larger community networks. One example is my mid-level survey course, “The Great American Short Story,” which was composed primarily of rising seniors, each coming from a different discipline, such as public policy, psychology, theater studies, and mathematics. We visited the Rubenstein Rare Book archive to study the various publishing technologies influencing the short story genre, from nineteenth-century gift books and periodicals to modern anthologies. Students gave presentations sharing their analyses of these texts as material artifacts, positing how the physical affordances governed the way readers interacted with the short story (see “Great American Short Story” Course Evaluations, my final course taught at Duke). My “Walden International” course was an advanced composition course taught at Duke Kunshan University, Duke’s partnership university in China. With ten students in one section of this class and twelve in the other, the course primarily included Mainland Chinese ESL students with a range of disciplinary interests, such as industrial engineering, humanities, library science, and journalism. This course postulated that Thoreau’s book speaks to an environmental and industrial transformation in antebellum America analogous to China’s twenty-first century transformation. Although the class began with students reflecting on their cultural, national, and gendered responses to a Walden Pond digital fieldtrip, it ended with them creating and posting their own videos—called Walden Pond in Kunshan—to YouTube, revising Thoreau’s words to describe the modern Chinese environment (see an example of a student’s Walden Pond in Kunshan project). My themed seminar, “When the Earth Speaks: Voicing the Landscape in American Literature,” was organized around cultural responses to disasters, from the 1755 Cape Ann earthquake to global climate change. The students in this introductory non-major English class ranged widely, from those taking among their first courses in the humanities to one student completing a Master of Arts in Teaching. In their final project, students engaged a variety of intellectual communities, from cartoon design to creative writing. Their goal was to voice our present environmental moment of acidifying oceans and rising sea levels through creative projects that sought to capture the felt impact of these environmental events. One student, for example, created a photojournalism website analyzing the Anthropocene’s local impact in North Carolina’s Piedmont region.

While there are many more ways I connect students with the wider community, such as my practice of bringing classes to local art museums to examine paintings and photographs contemporaneous with the literary texts we’re reading, I’d like to focus on my dedication to the scholar-teacher model. I have an ongoing commitment to sharing pedagogy ideas within communities of teachers. In addition to the forthcoming book chapter in The Pocket Instructor: Writing, a lesson for teaching the close reading of poetry was featured in the first anthology devoted to active learning techniques in the literature classroom, The Pocket Instructor: Literature. In the realm of digital humanities, I created a collaborative book with Cathy Davidson, Field Notes for 21st Century Literacies: A Guide to New Theories, Methods, and Practices for Open Peer Teaching and Learning (see the print version). In addition, I’ve shared my reflections on teaching Thoreau to ESL students in an invited lecture at the Huntington Library, as well as an invited article on the “secret” of good teaching for Duke Magazine and a forthcoming teaching roundtable in The Concord Saunterer: A Journal of Thoreau Studies (see the program for the Huntington lecture; see the full Duke Magazine issue). As a participant in the NEH Institute for College Teachers in Concord, Massachusetts, I learned how to more effectively teach the theme, “Transcendentalism and Reform in the Age of Emerson, Thoreau, and Fuller.” As a fellow in the Preparing Future Faculty program, I’ve learned how to effectively balance teaching, service, and research in a variety of institution types, from private liberal arts colleges to public universities. For me, teaching is both a classroom practice and a scholarly pursuit, and I hope to continue honing my skills by continuing to explore this intersection between teaching and scholarship. Whereas much of my exploration of this intersection involves writing about the classroom, I would like, in the future, to find ways to involve more students in collaborative scholarship, such as co-authoring essays or organizing and hosting panels and symposia. Placing scholarship and teaching together can only improve both practices, as I strive to be a more reflective teacher and a more collaborative scholar.